|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CAP - COMPUTER AIDED PAINTING IN THE THIRD CHAMBER

(Artistbook) published in the Salon Verlag, Cologne, 2000

CAP - COMPUTER AIDED PAINTING IN THE THIRD CHAMBER

Susanne Leeb in Conversation with Bittermann & Duka

Susanne Leeb: Your work involves landscape gardening and Utopian gardens in a large-scale project trading under the name of 'The Third Chamber'. You present your proposals for gardens as wall displays, in that you arrange, on a wall surface defined by colour, all kinds of images around one common idea – painting, emblems, storyboards and slide projections. How does the computer fit into your work as a hyper-medium, with its networking structure?

Bittermann & Duka: The wall displays are influenced by the way computer games are built up, and by the pattern of the CD-ROM. This clicking into a subject, which we stage on our surfaces, doubles as a filtering tactic and an invitation to play. You can move about in front of the wall surfaces and there‘s no linear narrative structure, only different, interlinked stages of visualisation. The fact that they can be laid out on a desktop is also a production factor, though. The whole mural is designed on the computer. The colours are mixed at a computer-controlled colour-mixing station, and are attuned to each other via charts. That enables you to work with great precision and to exactly relate the various constituents to each other.

Susanne Leeb: So when you‘re aiming to present a garden project, you could, theoretically, stay right there in virtual space and produce CD ROMs. What do you gain by translating computer-generated sources into wall displays?

Bittermann & Duka: For one, that they relate physically. With the wall displays, which may be composed like garden plans in any case, that experience of entering a picture as if it were a garden becomes a much more realistic and vivid proposition. Then again, once you‘re painting, you are not dealing with virtual reality any more, nor with a model putting your case for its being realised, as in architectural competitions, for instance. The murals stand for themselves. The gardens do not exist, true, but the picture as an object is real. So painting keeps the represented gardens in a potential state for us, somewhere between a game, fiction and reality.

Susanne Leeb: You have been using the Bryce programme for some time now to generate virtual landscapes. Then you take the prints as guides for your painting. What attracted you to this programme, and what has changed for you in terms of picture-making?

Bittermann & Duka: For some years now, computer image generating has been getting more and more sophisticated, and for all the virtuality, the quality is almost photo-realistic; added to which, the user surfaces with their knobs and buttons look almost as if they were analogue. So we achieve results faster and more simply. The element of chance in a game also produces constellations that would be impossible to conceive other than by computer. That kind of chance effect then has to be re-integrated into a specific, meaningful context, and in our case, working on the garden phenomenon and 'The Third Chamber'- project are a guarantee that it will be.

Susanne Leeb: But doesn‘t this huge stock of potential pictures also make the decision-making processes harder? What is your criterion for the best picture?

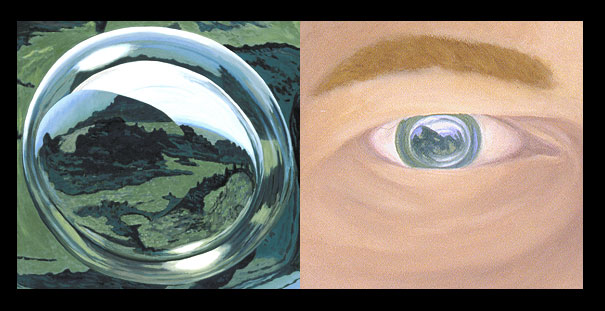

Bittermann & Duka: The initial determining factor is the concept we develop in advance as to the kind of garden or landscape to opt for – whether we want to realise a fictitious place or one that exists in reality. As soon as that is settled and we are sitting at our computer, it becomes a largely intuitive process. The screen gives us the frame through which we view a virtually constructed landscape. We can then travel through this landscape with the virtual camera and decide on the best angle for a rendering. There is hardly any difference between this and the painters of the eighteenth century looking through a Claude mirror, or the viewfinder for a photographer. In addition, of course, you have accumulated visual experience from observing nature; you‘re familiar with the history of landscape painting and have a store of general pictorial experience that always flows into the work process at the computer screen anyway.

Susanne Leeb: So you base your choice of the most suitable angle of vision on perceptual conventions informed by more traditional landscape painting, certainly not by the computer. But you have a feedback-effect from the computer into landscape painting. With some few exceptions, the illusion of three-dimensional space has not been a particularly prominent feature of painting in the twentieth century, has it? Now, you use these 3-D programmes to restore to painting a kind of pictorial space that, unlike photo-realism, does not betray the transfer between the two media. Can you reconcile that?

Bittermann & Duka : The main purpose of constructing pictorial spaces digitally is to raise the visual credibility of the pictorial invention.- The landscapes we make are partly montages in which we integrate other elements such as Utopian architecture or ideal notions of places. With the landscape generator, we can adapt imported objects to the 3-D landscape, simulate the same lighting and embed them in the atmosphere we want, so that our pictures become coherent in themselves. The reason this form of credibility or illusionism is important is that even though some of the landscapes or gardens we paint can really be laid out, for the moment they only exist as images. To persuade the viewer that these gardens are possible, it is important for us to have elements of pictorial rhetoric as offered by the simulation at hand. So we do exploit the conventions of perception that grew out of pre-modern painting and photography as well, quite consciously; our aim is less to break with the conventions than to have them work for us as picture-making aids.

Susanne Leeb: How closely do you adhere to your visual source and to what extent do you develop the pictures out of the potential inherent in painting?

Bittermann & Duka: That depends on the individual picture. But it is always an interpretation of the source through painting. It‘s just not possible to create certain structures except with oil paint and a brush. A computer print-out can amaze the first time round. But very soon it becomes a stereotype, and you‘re moving within pre-set patterns. With painting, you can overcome this, because it is possible to vary in style and apply such variations specifically. The colours are limited in a computer, too. Three primary colours from which the processor colours are mixed are simply no big deal if you‘re used to the spectrum of colour painting offers.

Susanne Leeb: Although Bryce is good for creating quite futuristic images and, in theory, your gardens, too, could be laid out some day, and some will be, the impression I have when I look at your pictures is more of a past future. Why is that so?

Bittermann & Duka: It might be because we work with many kinds of visions of the future, including historical ones. What we find interesting is the whole principle of sliding from the impossible to the possible, this interstice or passage. Jules Verne‘s mechanistic moon capsule is in our sights just as much as the architectural visions of a Bruno Taut or 1960s space design, which, under that futuristic skin, lacked many of the technological possibilities they were claiming. For painting itself and the garden aspect, we discovered a different kind of futuristic vision in Hubert Robert, a painter and landscape gardener of the eighteenth century. He did a painting of the Louvre, which had yet to be converted then, in such a way that his plan to introduce a new skylight could be seen and understood. Moreover, he simultaneously anticipated the Louvre as a ruin. This pre-modern tradition of painting is what we are involved with, especially when its subject is the garden. We quote these styles in order to create specific moods, quite consciously. Not that our relationship to that tradition is a nostalgic one, it‘s more explorative than that. The 'picturesque' quality, for example, without which there would be no garden history, has been utterly devoured by the kitsch industry. You‘ll find it in computer games, too. When you see, say, Lara Croft running through rank proliferating jungle or dungeons and ruins, these computer-generated spaces are movable props from that pre-modern painting. In our attempt to make such elements arable again for our own painting in the sense of 'computer-aided painting‘, we are playing with contemporary concepts of a picture rather than with past forms.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|